Lividity is when someone dies and the blood pools in their body based on the position they’re in. The skin turns dark. Philip was dead in his room for two days. He was lying on his back when his friends found him. One of the things I tortured myself about for months was thinking about what his body looked like, how all the blood had pooled on the back of it. I wished I’d never heard of lividity.

I knew that body wasn’t Philip any longer but it didn’t matter. I cried to think he was alone in his room for two days, to think that maybe he realized he was going to die and he was frightened; to think of him being handled by other people, put in a body bag, lying in the morgue. And now – I can look at it like he’s left this world and doesn’t get to live his life. Or I can look at it like he’s woken from this dream and so is spared the grief.

I’m grateful I wasn’t the one who found Philip. I used to wonder why we never see what a dead body really looks like, why the guy at the funeral parlor fixes them up first. You know what? Thank God. If I had to look at Philip in a coffin, better he looked like himself than what he looked like when his friends found him.

I thought about this because of an essay I read, which I’m linking to here.

My last post was a link, and I was about to end this one the same way. That’s not like me – and not that there’s anything wrong with linking. These two posts are just that good. But two in a row, plus not posting for two weeks, had me wondering, “What’s up with that?”

I started a ten-week writing class in January. It was hard to work on the assignments, as well as blog. Not because I didn’t have the time. Time doesn’t equal energy – I can only write for so long. And going from essay to blog post and back again was no easy transition. That would’ve been enough to deal with without my increasing frustration with the class. I had some real problems with V., the teacher. But that’s not the point. The point was I waited nine weeks to tell her what was going on. I acted like a resentful child, pleading sick when I didn’t want to go, until I went as far as I don’t want to write that assignment, and you can’t make me. And it’s not like I didn’t see what I was doing. I was paralyzed all the same.

Sometimes I think that since Philip died, what the hell else could bother me? Sometimes I think things bother me more because my emotional immune system is whacked. One thing’s for sure – his dying doesn’t give me a free pass. The things I was trying to work out before he died still have to be worked out. Like what went on in that writing class.

I’ve written about the way we take a situation – a set of facts – and turn it into a story where we’re writer, producer, executive director, star and victim. So if we see what we’re doing, we can stop, right? It’s that simple, but it isn’t easy. Some of my stories are old as I am, have a life and momentum of their own. It’s beyond thinking – my body gets involved. In fact, I’m not exactly aware of what I’m thinking because I’m consumed with reacting, wrung out and twisted and so terrified that I’m confused about what’s really going on or what to say about it.

So with V. I turned the problems I was having with her into she didn’t like me, wasn’t paying attention to me, wasn’t giving me what I needed. Blaming her rather than taking responsibility. Continuing the class with some secret hope that next time would be different, walking away pissed off and disappointed when it wasn’t. But why would it be? It was my version of “Ground Hog Day ” – doing the same thing over and over and thinking it’d turn out differently.

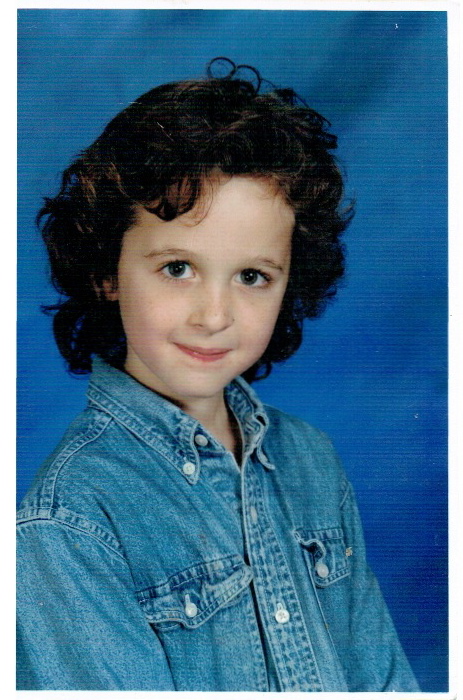

It didn’t help that I started class by announcing I wanted to use the assignments to write about something other than Philip. Did I forget who I was, who I am? That was a ridiculous and unrealistic pressure to put on myself because I do not want to write about something other than Philip. And what I write isn’t about “Philip.” It’s about me. What his death has done to me, what it feels like to live in the aftermath. This is hard, hard stuff. Writing’s a way I abide it. When I can abide it at all.

When writing is an assignment, it becomes a “have-to.” And it’s fine to say as a writer, I should be able to finish something when I have word count or a deadline. But I’m not living in a world of word counts or deadlines. I’m living in a world without. I don’t recognize it, I don’t like it, I don’t want it. When I’m with my daughter, when I’m at work, when I see Kirsten or Harriet, when I write – I crystalize. I feel it all, all of it. But then I’m driving or walking the dogs or sitting on the couch alone and it’s like trying to stand up in a rowboat during a monsoon.

It took nine weeks – as well as conversations with Ed, Kirsten and my daughter – for me to get the nerve to tell V. I wasn’t going to the last class. “I’m like a child,” I told Natalie, who tilted her head and stared at me with a face full of are-you-kidding-me? “What do I say?”

“How about that class isn’t helping you?” she answered.

Result? V. and I talked about what was going on, and while I still didn’t go to the last class, I was out of the drama around it. In other words, I realized V. was not my mother.

And as far as what I write about, V said writers write about what they can’t stop talking about. I’d say we write about what we want to keep talking about but have to stop talking about because nobody wants to listen. So we write for others to read because we need that connection. I’m not saying “nobody” wants to listen to me about Philip. But it’d be impossible for anyone to listen to all I need to say, as impossible as it would be for me to keep talking. My throat would be scorched from the all of it.

It’s not for me to say, “I’m not going to write about Philip.” This is my need. For now, the writing is writing me.

© 2014 Denise Smyth