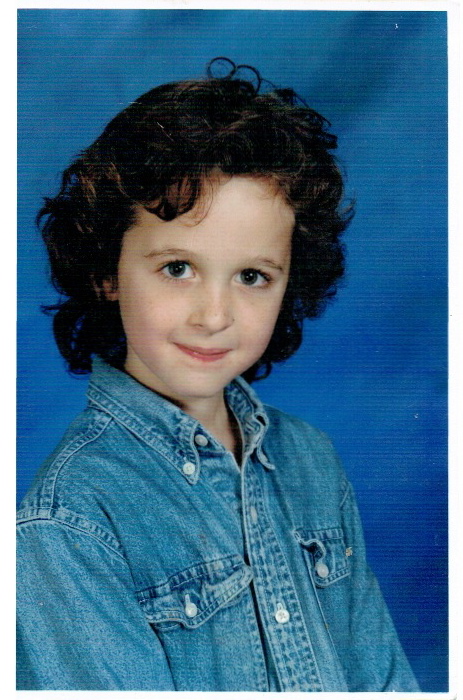

Philip at seven

Last week I walked into therapy, sat down and made an announcement.

“I want to have a baby,” I said.

“What you need to have is a man,” she answered.

First off, in case you’re wondering, the baby ship sailed about five years ago. Second, that’s not exactly what my therapist said; she’s way more subtle and nuanced. But it’s what she meant, and it’s not about being saved – it’s about what I need and how I take care of myself.

It’s not just having a baby. I want to feel the fullness of pregnancy, I want to walk in the world belly-first. I want to use words like holy and sacred and cherish and tell you I’m on hallowed ground because that’s what it felt like to carry my babies. I want the peace and wonder of those all-too-short nine months. Twice in my life, I used to think; only two times in a whole lifetime do I get to be pregnant. And maybe I’m remembering all this in a blue haze of sentimentality, but I’m longing for Philip and it’s making me crazy.

The need I feel doesn’t seem to be for a man; but I suspect I’m needing to hold and be held, and it’s easier to feel it for a child than an adult. Hence maybe it is for a man. But I can’t see it, not the way I see my child’s gaze, my child’s sleepy arms around me when I carry him to bed. I can’t see it. I’m an adult. If I’m yearning to be held, then I have to think about how that happens. I’m never going to be pregnant, not in this life. If I have a need, I have to figure out a realistic way to meet it.

I don’t know how I got on to that whole thing when what I wanted to write about is what I see when I look at that picture of Philip, and how there are times when I feel like his death is killing me softly and slowly. I try to write truthfully, to stay away from sentimentality, from victimhood. But when I look at this picture – and for some reason I’ve been thinking about it and staring at it for days now – I see an angel and I remember what a sensitive kid Philip was. I remember the way he used to toddle after me, even into the bathroom, how he’d cry if I closed the door. And I loved it because I knew it wouldn’t last. I remember the poem he wrote in second grade, where he named all his friends, but ended by saying that I was his best. I remember the day when we first moved to Montclair – he was seven, like he was in the picture – and I looked out my window to see him in front of our house, leaning on a telephone pole, watching my neighbor’s kid across the street. Jimmy was a year older than Philip. He was on his front lawn playing with what looked his entire little league team. Back and forth I looked with a tight stomach and sagging heart, knowing Philip wanted to be invited over, knowing that if they were letting him stand there, he wasn’t going to be.

But Philip got himself into that, and he’d have to get himself out of it. What parent doesn’t wish they could protect their kid from any-and-every-thing? But we can’t – and if we think about it, why would we want to? Because sooner or later they’re going to be on their own, and what then, if they’ve never figured out anything by themselves? And how does one live more deeply and with meaning, without having had to move through suffering in some way or another? Because not only don’t we get out of here alive, we don’t get out without grief.

When I look at that picture I see Philip at nine, at a pool party with his friends and their families. I see him coming over to me and Phil crying, because his friend Tim pushed him. He didn’t understand why Tim was mean – that’s what got to him. One by one the kids in the pool began looking our way and whispering. It’s that pack mentality that senses weakness – it’s the scent of blood, and they were circling for the kill. Philip’s weakness was wanting to belong but not feeling he did. Plus he broke the unspoken rule of not “telling” on another, a sin with a hard recovery.

Phil went to speak to Tim’s dad, who told him Philip should have pushed back. I think nine is a good time to tell your kid not to lay your hands on another kid if it’s not self-defense. But what do I know of a boy’s world? What I knew was my son was crying and everyone was watching. And what greater humiliation than to be the shut-out of the group, to be the kid leaning on the telephone pole, watching.

When we got home, I knelt down to talk to him. “Philip, look,” I said, “I don’t care if you cry. But those kids aren’t going to be nice to you if you do. Maybe you could try really, really hard next time not to cry, and just tell yourself you’re going to wait until you get home. Because here you can do what you want. Go in your room if you have to. Cry, yell, whatever. But don’t give them any reason to make fun of you.”

I was begging him, really, to let it go, because then I could feel better. You know how it is – your child doesn’t hurt without you hurting right along. But it didn’t work. Philip was upset and didn’t say a word. So I stopped talking and stepped back because this was something else he was going to have to puzzle out on his own. And I had to trust that he would, and that both of us were going to be all right.

And that’s not all I see, but it’s all I’ll talk about for now.

© 2014 Denise Smyth